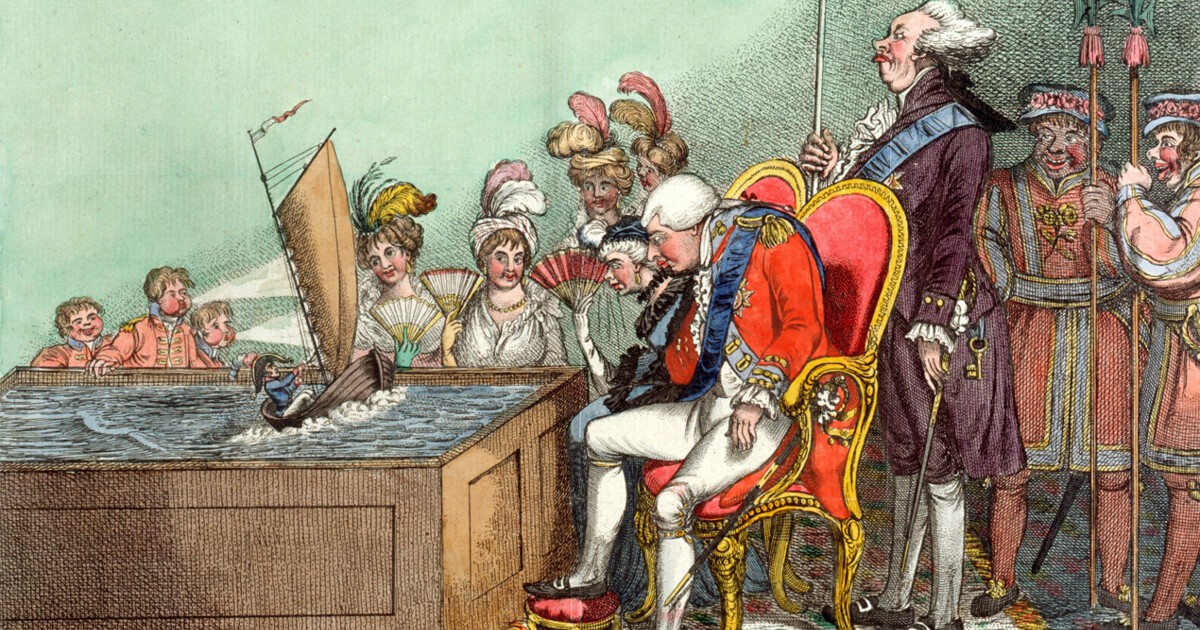

Satire is a great angry sprawling mass. It’s one of those literary phenomena which is impossible to define but which most people recognise when they see it – unless they’re as dim as the Irish bishop who is supposed to have said of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels that ‘for his part he hardly believed a word of it’ (‘hardly’ is a deliciously bishoply way of hedging his bets). Satire is a slippery beast because it’s often treated as a ‘mode’ of writing rather than a genre, or (in less technical language) as an adjective rather than a noun. You can have a satirical version of more or less anything – a satirical novel, a satirical play, a satirical car advert, a satirical news programme. But it also has some of the characteristics of a literary genre, particularly through the long and various tradition of verse satire. That tradition has big-name reference points: Horace and Juvenal and Persius and Boileau and Scarron and Pope and Byron. By the late 16th century in England, verse satire deriving from Latin originals had definitely come to be regarded as a distinct literary kind. A century or so later it had become an institution, as a group of mostly conservative and often Catholic satirists claimed to belong to a virtual dynasty, as though operating within the genre of verse satire were a matter of literary genetics and paternity: Dryden’s ‘Mac Flecknoe’ and Pope’s Dunciad both present their own satirical lineage (as sons of Horace or Ben Jonson) in parallel to a downmarket genealogy of dunces, in which (in Pope’s words) ‘Still Dunce the second reigns like Dunce the first.’ Those satirical dynasties were themselves satirical inversions of political dynasties, of dim Hanoverians or sexually promiscuous but infertile Stuarts.

Even verse satire can be unruly, though. Satires and lampoons scrawled on odd pieces of paper by poets who are drunk or angry can fall into the wrong hands. So, the story goes, the Earl of Rochester (who liked to be thought of as more often drunk than sober) accidentally gave a copy of his satire on Charles II (which includes the immortal line ‘His sceptre and his prick are of a length’) to Charles II. Verse satire can be formally unruly too. It has often been written in open-ended verse forms that offer no particular incentive to stop, like the couplet or the Latin hexameter or the endlessly replicable ottava rima stanza, rather than self-contained poetic structures like the sestina or the villanelle (though doubtless someone will have written satirical versions of those forms, since reluctance to follow rules is an important feature of satire). Open-ended verse forms became a natural habitat for satire because the satirist often wishes to insist that there is an unending series of objects which need to be attacked, and that there is no particular reason to shut up at the end of a poem except for running out of breath or paper. Verse satires can take the form of a grotesque parade of dunces, in which one (say, a fop who loves his ruffs and collars) struts onto the stage then vanishes into the gloom or falls into a ditch, while another (a dancing master, maybe) skips into the limelight. The Elizabethan satirist John Marston was repeatedly mocked for his line ‘Let custards quake, my rage must freely run,’ but his opposition between a wobbling but self-contained cowardly custard (he is thinking of a set custard rather than a sauce) and his own free-flowing inspired ‘rage’ does convey the bank-bursting anger of the satirist, who is inspired by the awfulness of everything to spew a stream of anger at it all. In Marston’s case the awful included himself, whom he despises almost as much as everyone and everything else, except perhaps for the flickering light of reason.

The targets of satire are unlistably numerous, but they include affectation, foppery, political corruption, smells, cardinals, publishers, low churchmen, high churchmen, turbots, gluttons, women, old men, courtiers, emperors, bores, Margaret Thatcher, fools, bad poets, frocks, personal enemies, Robert Walpole, reason, lust, excrement, travel, ex-soldiers, Americans, patrons, opera, religious orthodoxies, sexual deviants, shopkeepers, dildos, merchants, political parties and all self-deluded asses who believe themselves superior to the rest of humanity. When Gulliver described the land of the rational horses called Houyhnhnms he presented a catalogue of things absent from that nation, which is more or less a satirist’s shopping list of potential targets: there were ‘no stupid, proud pedants; no importunate, overbearing, quarrelsome, noisy, roaring, empty, conceited, swearing companions; no scoundrels raised from the dust upon the merit of their vices, or nobility thrown into it on account of their virtues; no lords, fiddlers, judges, or dancing masters’. As Swift’s dim bishop might say, it’s hardly possible to believe that a nation which entirely lacked the objects of satire could exist on this earth.

To think of a satirist as a person who angrily turns against a gale-force wind and sprays liquefied shit at a group of constantly multiplying targets would not be entirely wrong. The truly misanthropic, universally and riotously angry satirist can perform acts of harm which are also acts of self-harm, as their imagination fires itself up with a disgust that is also a form of self-disgust. The description by Swift, that great master of self-disgust, of the way the Yahoos (the filthy underclass in the land of the Houyhnhnms) treat political favourites who have fallen from grace is a self-hating representation of the satirist’s art: ‘all the Yahoos in that district, young and old, male and female, come in a body, and discharge their excrements upon him from head to foot.’

More decorous and less self-loathing satirists than Swift are, of course, available. There is Horace, whose dialogues with baffled interlocutors invite the descriptor ‘urbane’, whose verse epistles brought a strand of philosophical reflection into the wider satirical tradition, and whose Sabine farm became for many an emblem of a self-contained philosophical life away from the hurly-burly of Roman politics. There is also an almost infinite number of satirists who had one particular target in view – a specific politician, or some more or less parochial storm in a teacup. In 1759 Laurence Sterne wrote a satire called A Political Romance about the allocation of an office called the Commissaryship of the Peculiar Court of Pickering and Pocklington in Yorkshire. His satirical pamphlet solemnly presented itself as an allegory of international affairs, but was also in a near literal sense parochial (to do with parish affairs), because it described how personal rivalries within the diocese of York had been blown out of all proportion. But it started Sterne off on the pathway towards his satirical novel, or perhaps even satire on the novel as a form, Tristram Shandy. Then there are satires that combine all of the above. Alexander Pope, for instance, could be scatologically self-abusing, direct cold blasts of fury against particular London publishers and squirt venom at what he saw as the generation of Hanoverian dullards who ruled the realm, while simultaneously forging lasting works from a civilised conversation across time with Virgil or Horace.

The only way to write a history of this ungovernable mode of writing is to decide that some things belong in it and other things don’t. Different decisions about where the centre of satire lies would produce very different canons. Focus on the satirist as the creator of loud and ultimately self-destructive personae and Byron’s Don Juan, with its artfully innocent hero and world-weary narrator, would seem like the apotheosis of satire. Oscar Wilde would be another exemplar, as a person who decided to live a life which did not simply satirise but self-destructively defied the sexual proprieties of late Victorian society. If a historian of satire saw it chiefly as a vehicle for allowing hatred of the times to interpenetrate with a universal misanthropy, then Swift would sit fuming in the middle of that history.

Dan Sperrin focuses on political satire, and his book has a scale and chronological range that borders on the exhausting. It begins in Rome, ventures boldly into Anglo-Saxon England, progresses through satirists such as Walter Map (under Henry II) and Chaucer (under Richard II), through the attempts to reanimate classical verse satire in the late Elizabethan period, on (at length) through the 18th century, right up to Armando Iannucci’s The Thick of It. Sperrin sees satire as being ‘primarily concerned with regime-level insecurity’, so ‘politics’ for him doesn’t include interpersonal or sexual politics: it means what kings, queens and ministers of state got up to. Each phase of his narrative begins with a sketch of British political history which emphasises links between the insular high politics of England and global, or at least European, affairs. These introductions are themselves the products of an immense labour of synthesis. The book’s gaps (it is weak on the reign of Mary I, for instance) usually reflect shortcomings in the existing scholarship of the topic, which Sperrin seems to be able to consume in bulk. At the centre of the book is a massive trio of chapters on Augustan satire and the age of Walpole. I don’t know anyone who would not learn a lot from his narrative history, nor do I know anyone who would not feel a bit weary after reading it all. Along the way there are some powerful descriptions of individual satirists. The Earl of Rochester is described as ‘a nasty, invasive and impudent figure roving the devolved power structures of the patrician cabal’, but also as a ‘Baroque’ artist, in Benedetto Croce’s sense of someone who aestheticises sin, and that’s a good way of thinking about a poet who could write with controlled passion about how vile it is to be human:

Were I (who to my cost already am

One of those strange, prodigious creatures, man)

A spirit free to choose, for my own share

What case of flesh and blood I pleased to wear,

I’d be a dog, a monkey, or a bear,

Or anything but that vain animal,

Who is so proud of being rational.

But there are losses as well as gains in Sperrin’s history. Coffee nerds describe some coffee grinders as ‘unimodal’, which means they produce an extremely even grind, and so foreground one particular flavour. This is great if you happen to enjoy that one taste. Sperrin’s book is unimodal in this sense. It is all about politics, and, as he puts it ‘I have (in general) chosen not to speculate about the substantial and important role that laughter may have played in the immediate and long-term reception of this literature.’ So this is a history of satire without the jokes.

Sperrin derives his method of interpreting satirical texts from Quentin Skinner. He, like Skinner, aims to identify what a given text is aiming to ‘do’ within its immediate political context. Skinner’s way of interpreting works of political theory has achieved remarkable and perhaps even excessive success. It underpinned Skinner’s larger project of treating the history of political thought not as a great tradition of texts which relate abstract truths, but as a series of interventions which were trying to do particular things at a particular time. Skinner’s influence on literary historians has been extensive, but it can carry a high price tag. Poems read in a Skinnerian way can sometimes seem like unimodal laser-guided objects, from which trivial details such as comedy or style or rhythm or confusion are flayed off (or perhaps ‘skinnered’?), so that the critic can explain what they were trying to ‘do’ in the precise context of October 1726. In our politicised age this method of interpretation – which implies that poets can do things with words, and hence operate as agents within a wider political culture – has appealed to a generation of literary critics who want to insist on the seriousness of literary study. That’s understandable: in a period obsessed by quantifiable research outputs and dominated by governments who only value art insofar as it contributes to GDP, no one employed by a UK university would want to confess that it can be quite fun when poets behave as though they are ineffectual angels who beat their luminous wings in vain. To hell with beauty! Damn laughter! Insist instead that poets do things!

Sperrin’s treatment of satires as ‘purposeful strategic interventions’ might seem like a good way of thinking about them, since satirists do often seem to want to do things, like turning public opinion against Mrs Thatcher, or reforming the English Church or destroying the reputation of a rival. His emphasis on political activism leads him to propose some potentially big shifts in the relative valuations of several English satirists. Tory Catholics such as Dryden and Pope are, if not deposed from the monarchy of wit, then at least demoted from absolute rule over the tradition that they claimed to dominate, while Sperrin foregrounds an alternative satirical tradition which was typically Whig or nonconformist or reformist.

There is plenty of material that might fit into such a tradition. The prose satires of the Elizabethan Presbyterian author who called himself (or themselves) ‘Martin Marprelate’ had a freewheeling energy. He accosted Elizabethan bishops with words such as ‘bumfeage’ (which probably means something like ‘whip the arse of’) and with such comic success that the ecclesiastical establishment was prompted to enlist Thomas Nashe and others to answer Marprelate in his own style. Andrew Marvell’s tolerationist work The Rehearsal Transpros’d of 1672 became a reference point for later reforming satire, and Sperrin argues that Samuel Garth’s mock-heroic poem The Dispensary (1699), about the reform of the apothecaries’ union, should be thought of as a political allegory in the Whig tradition of Marvell. Garth is certainly a more interesting figure than his critical reputation would suggest. But Sperrin is surely putting a politically motivated finger on the scales of valuation when he prefers him to what he terms his ‘underpowered and politically excluded Catholic imitator Alexander Pope’. Sperrin accuses Pope of not having offered ‘extended criticisms of the regime’s international failures’, and his later works are described as ‘internally incoherent’, which to many ears might be roughly equivalent to ‘interesting’, but to Sperrin means something like ‘lacking in a clear political purpose’.

The problem for Sperrin’s historical narrative is that the nonconformist tradition of satire didn’t achieve very much. It flounders with Defoe, since as Sperrin confesses (and it’s an understatement) ‘it is difficult to bring Defoe’s politics into focus with complete clarity.’ Even under the long and widely hated ministry of Robert Walpole (described by many as a ‘Robinocracy’ or rule by robber Robert), oppositional satire didn’t manage to get people thronging to the barricades. ‘The Walpole phenomenon demanded a serious rethinking of satire itself as a counter-ideological force that could operate from a position of disaggregation and frustrated peripheral resentment.’ But it’s not clear that this ‘serious rethinking’ either occurred or had a long-term effect. So Sperrin is left confessing that Whig satire, ‘like the constitutional infrastructure that had brought about the Hanoverian succession, was possessed of the acute melancholy of overdetermined perpetuity. It was unable to make of itself a high-powered Anglophone literature that could supersede ongoing self-commentary on the imitational and derived elements of its own style.’ In other words, it wasn’t very good.

Meanwhile pillars of the traditional satiric canon are, like Ozymandias, toppled into the sand. Don Juan is ‘petulant and imaginatively stagnant’, while Byron’s satires are ‘predicated on quite confused and imprecise readings of the ancient imperial canon’. Byron’s schoolmasters would no doubt have agreed with that judgment, but readers who have chuckled their way through the wild accidents of Don Juan’s life might wonder if describing Byron in this way is slightly to miss the point. Sperrin also dismisses Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest as ‘an unhelpful distraction for historians of this period’s satire’. Wilde’s satirical transformation of the clichés of romantic comedy was in its way a profoundly radical form of satire, which hinted that beneath every heterosexual late Victorian Londoner lurked a hidden life of homoerotic ‘Bunburying’, but radical sexual politics don’t meet Sperrin’s austere criteria for determining what is ‘political’. After 1848, satire ‘lost its position as a primary literature of state affairs in Britain’, and after Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (which brilliantly fuses the small-scale preoccupations of the courtship novel with an awareness of the interconnectedness of global financial markets) satire turned into a ‘politically desensitised, “humorous” and morally conservative literature’. Oh dear.

The disappointment with satire that emerges from this book is in part a product of its method. The alluringly simple-seeming question ‘What is this text trying to do?’ is a much less good one to ask of satire than it might sound. It immediately excludes the possibility that a satirist might be a confused mess of self-censorship mixed with odd lunges for freedom, in which a desire to make a mark on the world as an individual intersects riskily with a desire to make people change their behaviour. The question ‘What is this satire trying to do?’ also implies that authorial intentions are clear, and that so long as you know enough about the day-to-day politics of the Walpole administration you can pin those intentions down and label them like dead butterflies in a display case. Many of the most successful satirists – Evelyn Waugh, even dry old Orwell – had a streak of madness and self-contradiction within them which might lead them to answer the question ‘What are you trying to do?’ with something like ‘I’m trying to beat you all up and beat myself up too.’ Furthermore, asking the same question of satire that one might ask of a political pamphlet aimed at redressing an immediate political wrong radically restricts the parameters within which satire can operate. It makes satire a mode that addresses a particular moment rather than a mode which might have an afterlife, or even change how people see the world in the longer term. You might say that’s not just a recipe for disappointment with satire, but for missing the point.

Sperrin’s disappointment with satire is itself not hard to contextualise, however. It is a manifestation of the present political moment – when many people on the left want things to be done differently, but see the same old political arguments trickle grubbily down the same old cul-de-sacs to nowhere. State of Ridicule radiates the frustration of a politically committed reader who is trying to find a moment when a tradition of Whig reforming satire really got going and made the world better (it didn’t), or when satire toppled the ‘Robinocracy’ of Walpole (it didn’t), or when it brought down Thatcher (it didn’t), or, maybe, enabled the Reform Act (it didn’t). Satire doesn’t have a good history of doing things, but that may be because doing things is just not what it does.

There are many different ways of doing things in the world. Some are attempts at quick fixes. These usually don’t work. In 1979 I spent hours cutting out letters from newspaper headlines to make badges that looked like ransom notes which said ‘I hate Maggie.’ I gave one to my English teacher. The only consequence was that the English teacher was told to take it off by the headmaster. My labour ended in the bin, and Mrs Thatcher was elected, and remained in power for more than a decade. Satires with less narrowly political targets, paradoxically, are more likely to bring about long-term revolutions in taste or behaviour than satires which are written for one purpose at one moment. And humour is often the engine of these long-term revolutions, since satire can make things that other people take seriously appear laughable. That’s why authoritarians (and most headmasters) hate its radical unruliness. Cultural change can happen through the partial agency of literature, but cultural changes on the whole happen very slowly. They can be enabled by literary texts, but usually only when those texts seek to ‘do’ more than address their immediate moment – when they stick like a thorn in the flesh of a political configuration, and gradually persuade a generation born after their moment of production that the world ought to be different from the way it was.

Several of the satirists with whom Sperrin has least patience are those who best display the power of satire to accomplish things in the long term. Don Juan no doubt encouraged the odd Regency fop to be more foppish, and no doubt Sperrin is right to suspect the poem of being self-indulgent and insufficiently engagé, and of being founded on a superficial understanding of the political position of Horace to boot. But Byron encouraged people to think about freedom, in its entangled sexual and political forms, in Europe and beyond. And along the way Don Juan was extremely funny, and that insinuated Byron’s politics into the ethos of the next generation, and nudged outwards the boundaries which circumscribed the kinds of thing that could be read and said in polite society. That other satirist whom Sperrin dismisses as a ‘distraction’ to his larger narrative, Wilde, has through his posthumous reputation done as much to change public and legal attitudes towards homosexuality as any single overtly political action. Satire can be a powerful agent of those wider, slower forms of political and social change, though when measured against the immediate political intentions of its authors it can seem as though it has achieved nothing at all. But in this life you have to be patient. Things can eventually change, provided you make people laugh at the right objects.