On the 80th anniversary of Hiroshima, the world is no closer to containing the spread of nuclear weapons

“There is no absolute defence against the hydrogen bomb,” Churchill told the Commons in March 1955. “What ought we to do? Which way shall we turn to save our lives and the future of the world?” A month later, he was forced to hand over power to Anthony Eden. The 80-year-old PM was feeling his age: “It does not matter so much to old people; they are going soon anyway, but I find it poignant… to watch little children playing their merry games, and wonder what would lie before them if God wearied of mankind.”

This was disingenuous, to say the least. In 1955, Churchill was one of three men who controlled the world’s nuclear weapons: the other two were Eisenhower and Khrushchev. Britain had tested its first nuclear weapon three years earlier. The horror of Hiroshima was still fresh in people’s minds. The nuclear arms race was underway and God had nothing to do with it, although the Pope had been quick to condemn the atom bomb.

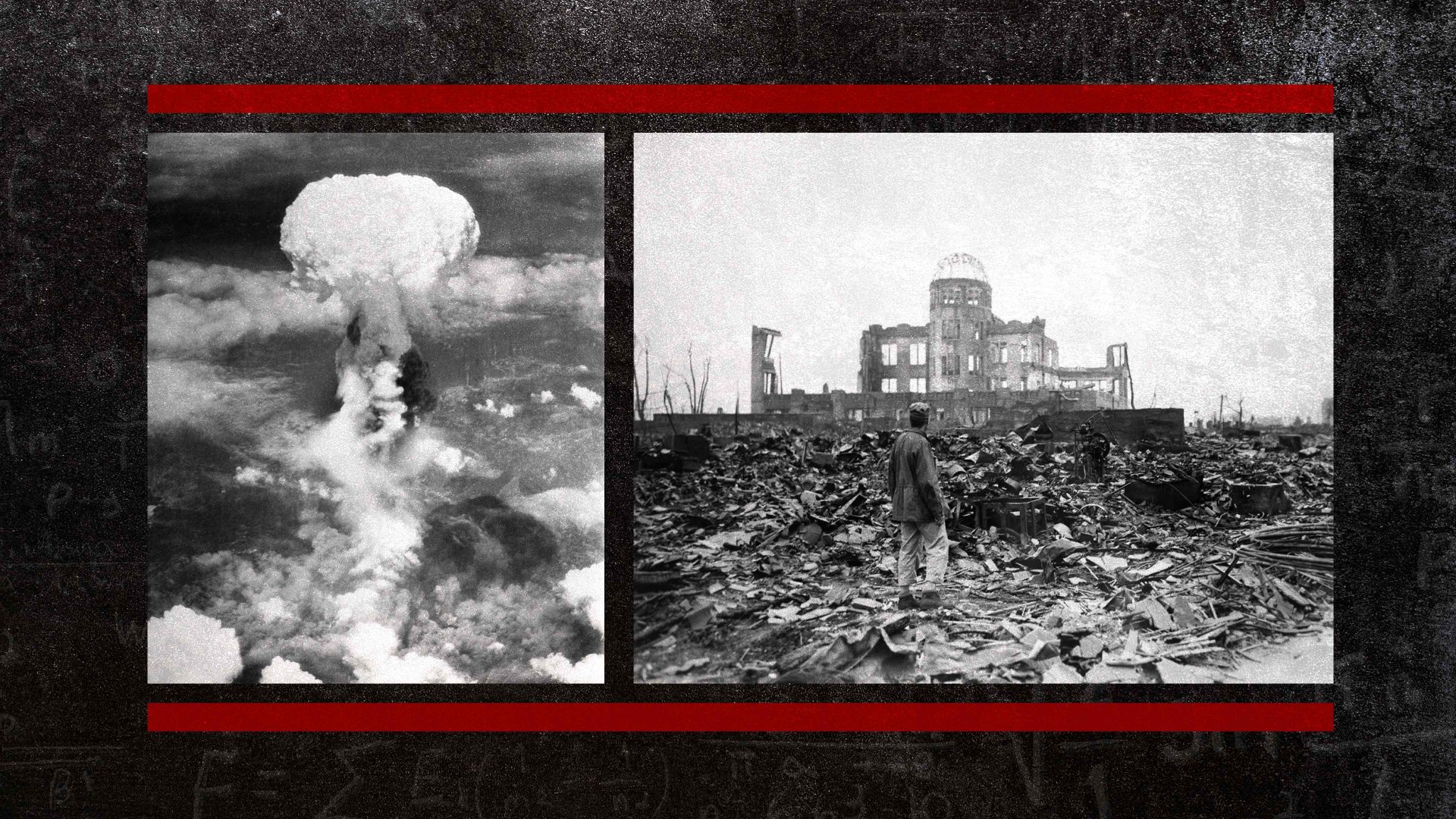

America had dropped the first one on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, and Nagasaki followed shortly afterwards. In Britain and America, the main emotion was relief. The atom bombs had done their job. Japan had surrendered. “The full effect of a single atomic bomb could be fairly judged to-night,” reported the Guardian – wrongly, as it turned out. In photos, “only a few skeletons of buildings are shown standing.” It took weeks for the first newspaper to publish a report from Hiroshima. The US had banned journalists from the region, but one Daily Express reporter managed to reach the remains of the city.

Wilfred Burchett realised that the initial blast, devastating as it had been, was not the end of it. Some people had survived the explosion. Now, “for no apparent reason their health began to fail. They lost appetite. Their hair fell out. Bluish spots appeared on their bodies. And the bleeding began from the ears, nose and mouth.” What Burchett called the “atomic plague”, and what we now call radiation sickness, was killing them.

The US authorities tried to dismiss his report as pro-Japanese propaganda. Then John Hersey filed his account of what six survivors had endured for the New Yorker. The article quickly became a book. The after-effects of the nuclear bomb were becoming apparent. And a terrible logic began to play out – a logic which, on the 80th anniversary of Hiroshima, is as powerful as it ever was: that the more horrifying this weapon was, the more indispensable it must be.

In the popular imagination, Hiroshima was an American production, and it was true that the Manhattan Project was based in Los Alamos. But it was in Britain that the initial breakthrough had taken place. In 1940 two German-Jewish physicists working at Birmingham University had shown that an airborne nuclear weapon was feasible. A year later, the UK and Canada set up a programme called Operation Tube Alloys: the boring name was a deliberate attempt to keep it secret. Then the US joined the war, and it was agreed that the nuclear programme should move to a safer location in America, away from the threat of German bombs.

Since Britain had played such a vital role in the development of the A-bomb, we assumed that the US would want to co-operate with us as it raced to consolidate its nuclear advantage. “With American and British scientists working together we entered the race of discovery against the Germans,” Truman had said, after ordering the attack on Hiroshima.

We were wrong. There were overtures, but the US was reluctant. The government absolutely refused to discuss the subject in parliament. In 1949 one MP asked: “Is it a fact that the Americans have told us quite positively that we are not to use the knowledge we have, and are not to be allowed to make the bomb?”

“The honourable gentleman seems to be better informed than I am,” replied the minister of supply. Actually, the MP was very poorly informed. Attlee had given the go-ahead for a British nuclear programme more than two years before, despite the fact the country was struggling to fund the welfare state he had promised them. “We’ve got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs,” Ernest Bevin reportedly said. “We’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack on top of it.”

Why? Did Britain really think it could take on the Soviet Union alone? Ironically, the calculation Attlee made was not unlike the one Keir Starmer is making today as he confronts the threat from Putin. He believed he could not necessarily rely on the US. Nato had not yet come into existence and it had been a struggle to persuade America to enter the second world war.

Attlee later recalled: “We couldn’t allow ourselves wholly to be in their hands, and their position wasn’t awfully clear always.” Britain might be a depleted, exhausted country, but it wanted leverage with the US, and only by acquiring the most powerful military technology in the world could it get it.

By 1952 we were ready to test our first bomb. Russia and America had wide tracts of desert to detonate their bombs in; we didn’t, so Churchill persuaded the Australian prime minister to let us blow up an old Royal Navy frigate off the Montebello Islands, just off north-western Australia.

The entire operation was recorded in a chilling film released by the ministry of supply. “It began on the rolling wealds of Kent,” opened the narrator, picturing the atomic research HQ near Sevenoaks and ending in a terrifying countdown. Even now, boats visiting Montebello are advised not to stay more than an hour and not to disturb any soil. Plutonium levels at the site of the test are 4,500 times higher than on the rest of the coastline.

Britain was the world’s third nuclear power. Now there are nine, and the UK is about to buy 12 nuclear-capable jets. What ought we to do, as Churchill asked? For 80 years, the answer has always been the same. Get the bomb, and keep it.