In 2016, Philippine Congresswoman Geraldine Roman became the first openly transgender woman elected to a national legislature in Asia. Her election received international media attention and was lauded as a sign of the Philippines’ progressiveness on both gender and LGBTQ+ issues.

Indeed, by many widely used metrics the Philippines routinely ranks among the top 20 most gender equitable countries in the world. The nation has had two female presidents, routinely achieves nearly 30% women’s representation in the lower house of Congress without the help of national gender quotas, and is the highest performing country in Asia as measured by the Women’s Political Leadership Index.

While these achievements are certainly worth celebrating, they do not tell the whole story. Such positive indicators of gender equality coexist with a considerable amount of gender-regressive legislation. The Philippines is one of only two countries in the world where divorce is illegal—the other country is the Vatican. Same-sex unions are not legally recognised. Sex education was not allowed to be taught in public schools until 2014. It took 14 years of concerted advocacy and organising by women’s rights organisations to overcome vehement opposition by the Catholic Church to pass the comprehensive Reproductive Health Bill that mandated sex education. And following the law’s passage in 2012, the Supreme Court delayed implementation for two years and struck down many of its key provisions before ultimately ruling that it was otherwise constitutional. Abortion and abortifacients remain illegal.

Furthermore, in the same year of Geraldine Roman’s momentous election, presidential candidate Rodrigo Duterte repeatedly bragged about being a womaniser, used the term “gay” derisively, and publicly “joked” about raping women. He won the 2016 presidential election by a considerable margin. The first trans woman in Asia was elected to national legislature in the same year and in the same country as a man well-known for his virulent misogyny was sworn into the highest office of the land.

These two realities illustrate a puzzle about gender and political representation in the Philippines. How does a seemingly persistent undercurrent of women’s marginalisation square with the fact that women are routinely elected in high numbers throughout the country’s political institutions? And why, despite such high levels of women’s representation, do many of the Philippines’ laws and policies fail to acknowledge and empower women as equal members of society?

The family as path to power

These questions are what motivated me to focus my doctoral research on the topic of gender and political representation in the Philippines. Based on my years of experience working in local and national levels of the Philippines Government, as a US Peace Corps Volunteer and then as a development specialist, I thought I had a clear answer: political dynasties.

I knew, for instance, that while Geraldine Roman’s electoral victory was remarkable and her bravery in the face of harassment, threats, and discrimination was heroic, it’s also true that her candidacy was powerfully bolstered by the fact that she hails from a long-established political dynasty. Roman was elected to represent the first congressional district of Bataan province on the west coast of Luzon—a district represented by her father from 1988 to 2007, followed by her mother from 2007 to 2016. Her uncle was also governor of Bataan for 17 consecutive years between 1986 and 2004.

Similarly, I knew that women only began entering the Philippines’ legislature in significant numbers after term limits were enforced. The 1987 constitution drafted and implemented in the wake of the collapse of Ferdinand Marcos’ dictatorship established strict term limits for representatives. Beginning in 1992, after any legislator sat for three terms they were required to take a term off. A clever workaround to this rule involved having a family member run for office to hold the seat until the term limit was reset.

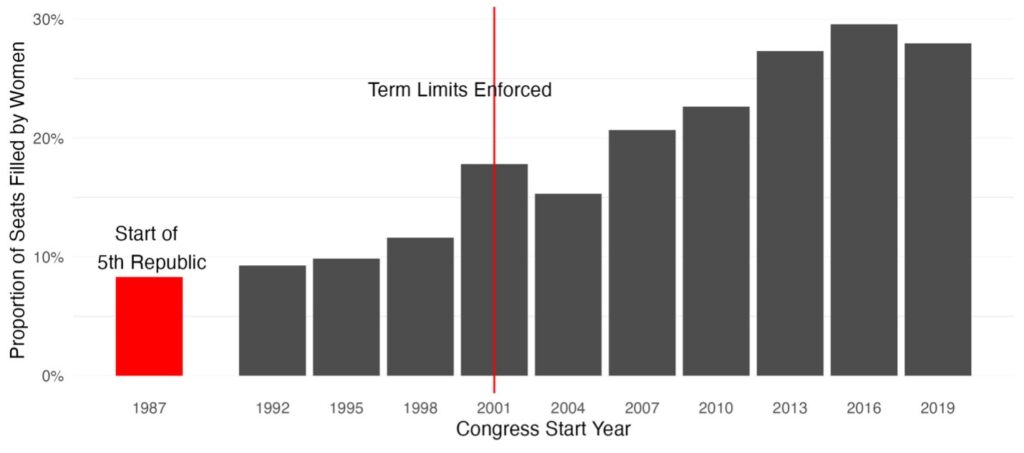

When these term limits were first enforced in 2001 and many members of Congress found themselves ineligible to run again, the number of women elected to the lower house nearly doubled in a single electoral cycle. A majority of the women elected were the wives, sisters, or daughters of male politicians who had reached their term limits. In the next election, many of those women stepped down and their no longer term-limited male relatives ran again for re-election. Figure 1 below illustrates this trend. The imposition of term limits, and the entry of so-called “bench warmer” candidates, therefore, jump started the Philippines on its path to achieve high levels of women’s representation in its legislature.

Figure 1: Average % of women in the House of Representatives, 1987–2021 (Source: Data compiled by the author from Philippines House of Representatives Archives, 2022)

Hereditary dynasties are powerful and pervasive players in the Philippines’ political system at both the local and national levels. Estimates among scholars about the exact percentage of women in the Philippines legislature with dynastic ties vary, ranging from as low as 12% to nearly 50% of the legislature depending on which time period is considered and the method used to determine dynastic ties.

To get a more precise number, I gathered rosters of legislators from the House of Representatives Archives. To do this I focused on the 283 individuals who were members of the Philippines Senate from 1987 to 2023 and followed a model developed by economists Marcel Fafchamps and Julien Labonne, which had demonstrated the validity of using last names to identify familial relationships based on the Spanish naming conventions adopted in the Philippines.

I identified last names shared by multiple representatives from 1907 onward to create a potential list of senators with dynastic ties. I then confirmed familial relations through secondary sources, including Tagalog and English newspapers, campaign and social media posts, and biographies to produce a more precise estimate of the number of senators from 1987 to 2023 who have clear dynastic ties.

I found that over 41% of all sitting Senators between 1987 to 2023 had clear dynastic ties. This finding is similar to a previous estimate that 45% of women in the lower house of the 12th Congress of the Philippines (2001–2004) had dynastic ties.

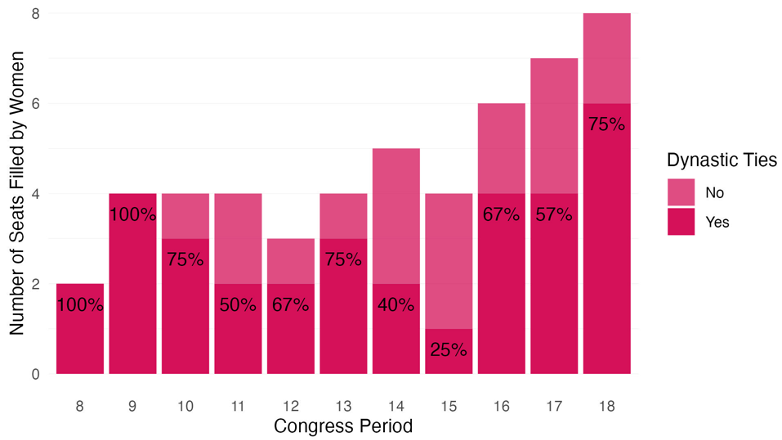

After disaggregating this data by gender, I found a pronounced difference between men and women senators. Among the men in the Philippines Senate 36.2% on average had dynastic ties during this time period, while for women senators, a majority (64.7%) had dynastic ties. The figures below show the levels of dynastic ties for men and women over time.

Figure 2: Proportion of men in the Senate with dynastic ties, 1987–2023 (Source: Data compiled by the author from Philippines House of Representatives Archives, 2022)

Figure 3: Proportion of women in the Senate with dynastic ties, 1987–2023 (Source: Data compiled by the author from Philippines House of Representatives Archives, 2022)

While male dynasts are also prevalent, as these figures show, a much higher portion of women had dynastic ties over time—over 50% of all women senators in all but two Congressional periods from 1987.

Dynasticism and interest representation

Why does it matter that so many women in the Philippines legislature have ties to political dynasties? In addition to the fact that nepotism is unlikely to result in the most qualified candidates, there is also good reason to believe that dynastic legislators will tend to prioritise their families’ political and economic interests.

Though this supposition applies equally to men and women, I hypothesised that women with dynastic ties would be less likely to represent the interests of women writ large. Shifting the patriarchal status quo requires activist legislation advocating on behalf of women as a group—but given that elite women politicians with dynastic ties have clearly benefited from the status quo in terms of their relative position in society, they have often demonstrated little interest in challenging social or institutional gender norms, or substantively representing the interests of lower-class women.

I hypothesised that since so many women legislators are political dynasts that they would be unlikely to advocate for the expansion of women’s rights and gender equality. To test this theory, I returned to the Philippines in 2022 to gather evidence from the House of Representatives archives. I collected records of all 63,000 pieces of legislation proposed between 1992 and 2019, records of congressional committee meetings about consequential bills on gender and women’s rights, and transcripts of parliamentary speeches. I then set out to determine if even under these conditions where a high proportion of women were elected to the legislature due to family ties and, therefore, I reasoned, without a clear incentive to represent the interests of women as a group.

The results surprised me. I found robust evidence through multiple analyses that women legislators—even many of those hailing from established political dynasties—still advocate for and act on behalf of women at much higher rates and in more innovative ways compared to men.

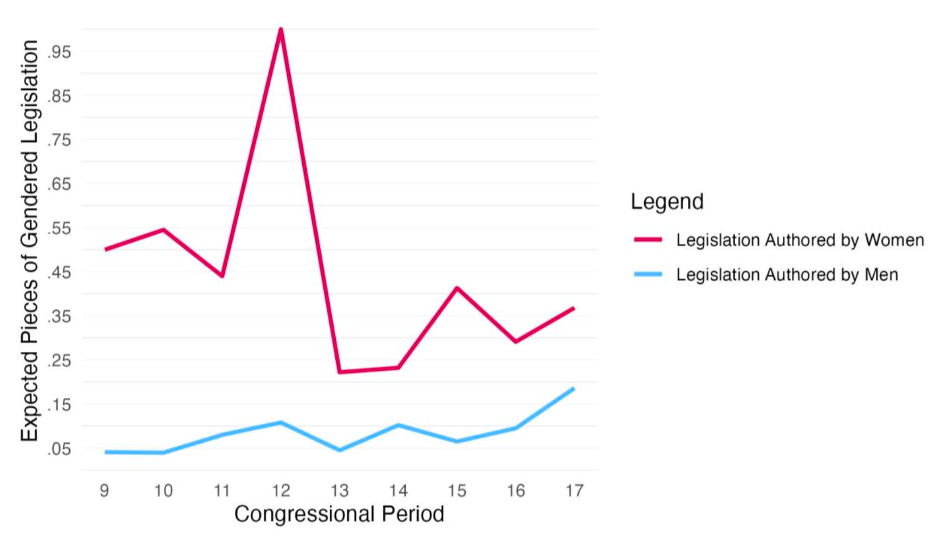

For instance, I found that women definitively introduce gender-relevant legislation at higher rates than men. To identify gender-relevant legislation, I observed committee referrals. After a bill is drafted and introduced into the House, it is referred to at least one of about 60 congressional committees organised by topic. The committee referral provides a clear signal as to the substantive content of a bill. I therefore defined gender-relevant legislation as any bill with a primary or secondary referral to the Committee on Women and Gender Equality (previously called the Committee on Women). The legislation in my dataset ranged from highly consequential bills like those mandating reproductive health access and equal pay for equal work, to more niche provisions like mandating accessible parking for pregnant women or lactation facilities in government buildings, as well as largely symbolic legislation like declaring national women’s holidays.

Using this categorisation method, I then calculated the rate at which individual women introduced gendered legislation compared to men. As this figure below shows, the difference in the rate at which men and women legislators introduced gender-relevant legislation is substantial in every congressional period.

Figure 4: Expected Proportion of Gendered Legislation by Author’s Sex (1992–2019) (Source: Data compiled by the author from Philippines House of Representatives Archives, 2022)

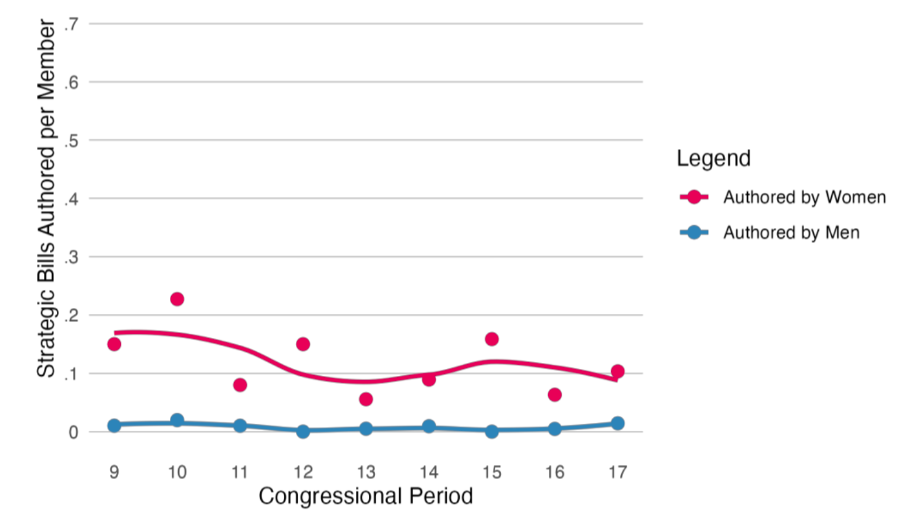

I also found strong support for the supposition that women consistently introduce more innovative legislation, which I defined as legislation that fundamentally challenges dominant gender norms. Because my previous analysis included the entire universe of gender-relevant legislation, I wanted to further determine if the legislation introduced by women specifically was more consequential or groundbreaking on average than the gender-relevant legislation introduced by men.

I drew on an established theoretical framework that differentiates between legislation on gender more generally versus “status policies”— a subset of laws that attempt to overturn social practices and systems that place women in a position of subordination and prevent them from engaging as equal members of society—to categorise legislation based on whether or not it strategically challenged dominant gender norms.

I labelled gender-relevant legislation as “strategic” if it did any of the following: 1) advance women’s political equality and inclusion; 2) reduce gender-based discrimination and remove barriers to equal employment/pay; 3) empower women as equal decision makers and rights holders in marital relations or otherwise challenge traditional heteronormative conceptions of marriage; 4) implement protections from violence in public or private places with clear enforcement mechanisms; or 5) increase women’s rights to abortions and contraceptives or otherwise empower women and girls in their reproductive choices. About 18% of all gender-relevant legislation fit my definition of being strategic.

I then computed relative rates at which women introduced strategic legislation for each congressional session compared to men. As the figure below shows, I found that women consistently introduced legislation that strategically challenged dominant gender norms at significantly higher rates than men. On average, women authored “strategic” gender legislation at 15 times the rate of men.

Figure 5: Rate of Strategic Gender Legislation Authorship by Sex (1992–2019) (Source: Data compiled by the author from Philippines House of Representatives Archives, 2022)

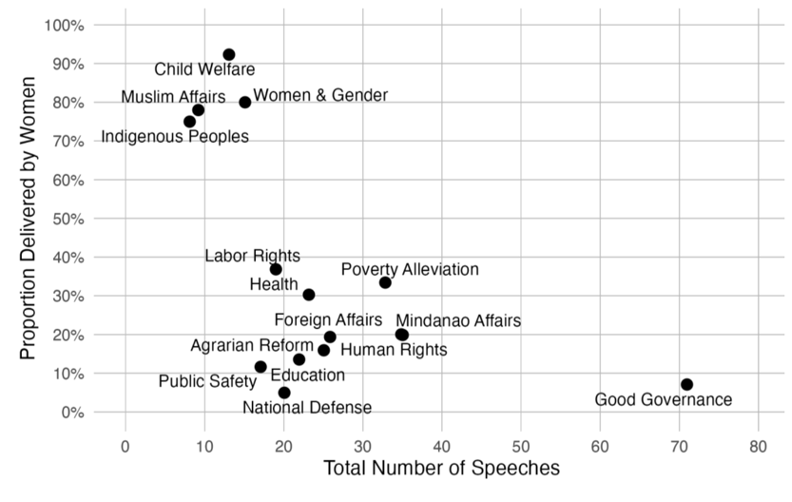

In addition to these differences in rates of gender legislation introduced by women, I also wanted to determine whether women legislators advocated on behalf of women’s interests and social equality more often than men. To study this, I constructed an original data set of over 700 “privilege speeches” delivered by 259 unique legislators in the 13th to 17th Congresses (2004–2016). The House of Representatives grants a Privilege Hour on Mondays when Congress is in regular session, during which time any member may speak “on any matter of general interest.” These speeches are used to communicate priorities of individual legislators, encourage colleagues to take action on an issue, or otherwise signal the preferences and values of the speaker to colleagues and constituents. They thus provide a window into the issues which women legislators choose to highlight and elevate to the level of policy discourse.

I categorised each privilege speech in my dataset based on its content and assigned them to one of 66 potential categories corresponding to which congressional committee they best fit into based on the speech’s topic.

Comparing the gender of speakers to the topics of their speeches showed notable differences between women and men. The figure below shows the top 15 most common topics, which accounted for 60% of all speeches in the dataset and demonstrates the gendered differences in speech topics. Notably, I found that women use privilege speeches to advocate for women’s interests significantly more often than men. And women are more likely to use their speechmaking powers to advocate for other marginalised groups in the Philippines, including children, Muslims, and Indigenous Peoples.

Figure 6: Gendered Patterns of Most Common Privilege Speech Topics (2004–2016) (Source: Data compiled by the author from Philippines House of Representatives Archives, 2022)

Another overarching conclusion from my research is that women legislators in the Philippines tend to demonstrate a more sustained commitment to authoring, introducing, and advocating for legislation which advances women’s interests. Women are much more likely to be repeat players when it comes to gender-relevant legislation, authoring more of this type of legislation and introducing different iterations through multiple congressional periods.

Through an analysis of congressional committee transcripts, I also found that in deliberations over legislation that had proven controversial among men, such as marital rape laws, women learned from previous efforts to pass such legislation and demonstrated a willingness to adapt their approach, modifying their arguments for the law as well as the language of the proposed law to ameliorate men’s concerns while still successfully passing the core element of the legislation.

Measuring women’s influence better

Sustained interest in policy relevant to women in legislative fora is often key to making headway in the legislative process. While this effort is not as easily detectable as an outcome—since it requires observing women’s contributions to shaping legislation across multiple congressional cycles—it is a substantively impactful consequence of increased gender diversity that merits further consideration.

Beyond suggesting new avenues for research on this topic, my findings also yield insights that may be particularly useful for civil society actors and gender equality advocates. For instance, committee meeting transcripts demonstrate how women legislators counter the dominant male narratives about gender relations.

Take, for example, the committee transcripts of legislative debates regarding marital rape laws. These transcripts show how women legislators successfully resisted the concern put forward by male colleagues that women might abuse the law by making false allegations. Women legislators capitalised on assumptions men had made in their deliberations about “typical Filipinas” being demure, using men’s own logic to persuade their male colleagues that this meant that Filipinas would be unlikely to make false claims of marital rape.

Studying these committee-level dynamics, and taking into account which specific arguments were successful in upending gendered assumptions, could help scholars understand where and how women are instrumental in shaping the debate over specific pieces of contested legislation and how potential conflicts among men and women legislators play out in committee settings.

But, since power accrues over time and is correlated with seniority and influence, it is also important to recognise that women are now, and may continue to be for decades, at a fundamental disadvantage within the power structure of legislatures even after achieving levels of representation that approach numeric parity. For example, I found that women were disproportionately excluded from committee chair positions relative to their numbers in the legislature until at least 2016.

New research shows how patriarchal attitudes and unfriendly institutions inhibit the success of female candidates.

03 December, 2019 Why good women lose elections in Indonesia

Observable outcomes, including committee assignments, the extent of participation in floor debates, and the successful passage of policy are all shaped by the gendered power structure of the legislative institution. Given women’s historical exclusion from politics, they are inherently more likely to be junior members of the legislature. Many processes may give preference, either formally or informally, to more senior members, and therefore women may have fewer opportunities to engage as equals in the legislature.

For this reason, identifying and studying forms of participation in the legislature that are equally open to junior as well as senior lawmakers has promising potential to better understand women’s legislative priorities and interests, which might be obscured in other modes of engagement that are not so egalitarian. My analysis of legislators’ use the Privilege Hour, which are available for use by all legislators regardless of seniority, is one example.

Indeed, this issue of structural inequality in legislative procedures raises the larger question of whether it is even reasonable to judge the success of women legislators based on the extent to which they succeed in getting legislation in favour of women passed. After all, evaluating women’s actions in the context of institutions where they are more likely to have fundamentally less power compared to men, may be an unreasonable standard. Women remain a minority in nearly every legislature of the world. Given that context, the passage of gender equality legislation in majority-rule institutions requires women legislators to not only author and introduce bills—they also must persuade at least some men to support their legislation.

An overemphasis among scholars and gender advocates on policy outcomes, therefore, places a considerable burden on women—and introduces a double standard in which women are held to account for their ability to successfully represent “women’s issues,” despite there being no similar parallel by which to judge the efficacy of men. It is worth thinking critically, therefore, about the ways in which the study of substantive outcomes might perpetuate the notion that women are less “effective” legislators, or inadequately living up to their gender mandates, when in reality the legacy of historical exclusion from political institutions and the highly gendered nature of legislative institutions continue to place women legislators at a relative disadvantage.

Given these conditions, gender equality advocates and civil society actors would do well to look beyond the passage of legislation, and should pay increased attention to proposed laws to understand how women can innovate through in subtle ways within the legislative process itself.

Lessons for policy

My research makes clear that even in a case where many women achieved office through nepotism rather than merits—and have competing class interests with a majority of women in society—women still bring an innovative perspective on issues related to gender and still tend to advocate on behalf of women more consistently and at higher levels than men. This finding lends powerful support in favour of institutionalised gender quotas. It suggests that in some ways it does not matter how women enter office, or even which women are elected: the inclusion of women in legislative institutions that have been dominated by men for decades is itself transformative and therefore worth pursing even through top-down initiatives like quotas.

However, mandatory quotas or women’s representation through nepotism should not be the final solution. It is important to note that even though women in the Philippines consistently acted on behalf of women at higher rates than men, it was still a minority of women legislators that specialised in this policy area. Not all women felt compelled to act on their gender mandates. Political corruption, nepotism, economic inequality, and wealth/opportunity hoarding remain serious problems in the Philippines, and simply including more elite women with dynastic ties is not a panacea to creating a more equitable and representative government.

Other dimensions of identity matter, as do the incentives of elected representatives, thus those other dimensions of representation should not be ignored in favour of putting too much emphasis on gender alone as a marker of descriptive diversity or as a promise of substantive outcomes. While getting more women into elected office is an important part of making legislatures and governments more representative, we should ultimately strive to create more equitable and inclusive institutions across a range of dimensions.

• • • • • • • • • •

This post is part of a series of essays highlighting the work of emerging scholars of Southeast Asia published with the support of the Australian National University College of Asia and the Pacific.