After two years of hunting, the quarry was in Jack Johnson’s sights. He had travelled across the world for this moment, tracking his prey as he hopped from country to country in an increasingly desperate attempt to evade him. Now, in the rising morning heat of Sydney, Australia, on Boxing Day, 1908, he looked across the makeshift ring at Tommy Burns, a man who had what Johnson coveted, the heavyweight championship of the world.

It was 11am when the 5ft 7in French Canadian they called the Little Giant of Hanover touched gloves with his opponent, nearly six inches taller and worthy of his nickname, the Galveston Giant. Despite the height disadvantage, Burns was the bookmakers’ favourite – possibly because of the power in his right fist, but more likely because Johnson was the first black man ever allowed to fight for the biggest belt in the business.

“I chased Tommy Burns around the world in order to get him into the ring with me,” Johnson wrote later. “I took on every potential contender between me and the champion. I virtually had to mow my way to Burns.”

Racial prejudice had stood in Johnson’s way since he won what then was termed the world coloured heavyweight title in early 1903. When Burns won his own title three years later, the clamour was already growing for a fight that would tell who really was the best heavyweight on the planet.

But the Little Giant ran, fighting other whites instead in San Francisco, New York, Paris, London, Dublin. After he unwisely told the press that Johnson was scared to fight him, the big man began to stalk him. There he was at ringside every time Burns fought and won; goading him, reminding him…

Now the bell sounded. “Here I am, Tommy,” shouted Johnson. “Who told you I was yellow?” By the time it rang again three minutes later, Burns had been sent to the canvas twice. Over the next 40 minutes, Johnson all but emasculated the world heavyweight champion. In the 14th round, with Burns unable to throw a punch and the 20,000 crowd growing restless, the local constabulary entered the ring, convinced that they would riot if Johnson knocked out his opponent.

What he wasn’t allowed to do in the ring, Jack Johnson accomplished in the following day’s newspapers. “Burns is the easiest fighter I ever met. I could have put him away quicker but I wanted to punish him. I had my revenge.”

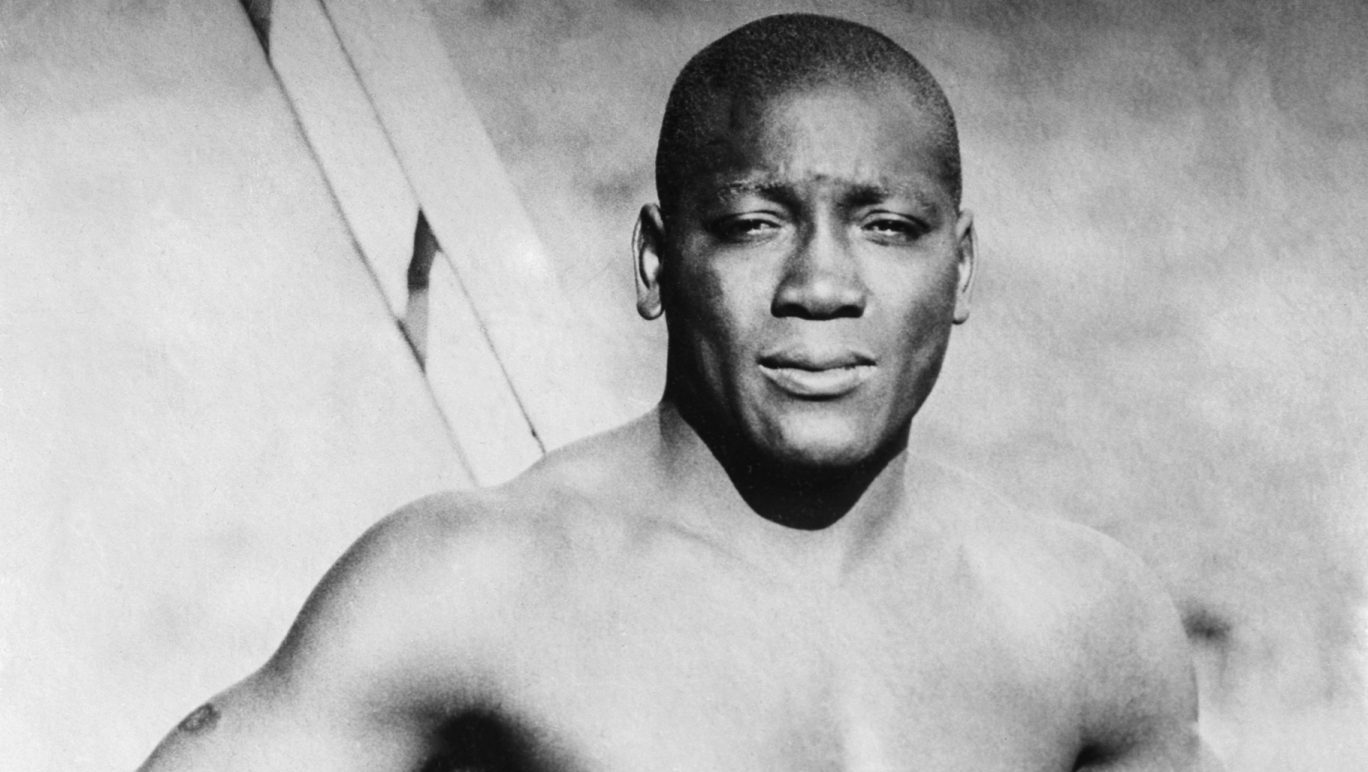

Jack Johnson also now had the world heavyweight title. It’s tempting to say that nothing would ever be the same again. However, the chaos that enveloped the champ, while new to his countrymen, had been his companion since childhood. Little wonder he thrived even as the world exploded around him.

“My life, almost from its very start, has been filled with tragedy and romance, failures and success, poverty and wealth, misery and happiness” – these lines from Jack Johnson’s autobiography In the Ring and Out provide a decent summation of a life that took him from the blood-stained cellars of Texas to a place in the sporting pantheon.

He was born John George Johnson in Galveston in 1878 to Henry and Tina, both former slaves. In a South that preferred to believe the civil war was still ongoing, there were few opportunities even for an autodidact like Jack whose limited schooling did not prevent him becoming an avid reader and keen student of the life and times of Napoleon.

Johnson’s size – closer to the heavyweights of the 1970s and 80s than to his contemporaries – decided his course. He began to spar while working on the docks in his mid-teens and by the time he turned professional in 1898, he’d fought in beer cellars and backrooms all over his home state. His list of scalps grew to include Britain’s first world heavyweight champion Bob Fitzsimmons, plus every great black fighter of the day from “Denver Ed” Martin to Joe Jeanette.

Following his earth-shaking win in Sydney, Johnson would take on allcomers, that was providing they were white – no one was willing to pay to see a black champion fight black contenders and besides, Jeanette et al would have provided far tougher competition than Al Kaufman and world middleweight champ Stanley Ketchel.

The one person the whole world wanted to see Johnson fight was James Jeffries, the former champ who’d retired from the sport undefeated in 1906. With everyone from former champ John L Sullivan to author and fight fan Jack London calling on “Big Jim” to regain the belt for the white race, Jeffries eventually went toe-to-toe with Jack in Reno on July 4, 1910. This “fight of the century” wound up being every bit as one-sided as his tussle with Burns.

At least Jeffries didn’t make excuses for his demolition – “I could never had whipped Jack Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have reached him in a thousand years.” There was one opponent, however, who would prove too much for Jack – the American legal system.

With his preference for white women, including white prostitutes, Johnson was a sitting duck for the Mann Act. At least he was if charges of “white slavery” could be levelled against him before the legislation had officially come into effect. Sentenced to 366 days in prison, Johnson promptly left the US for a decade in exile during which he lost his money, his enthusiasm and his title, the last to former cowboy Jess Willard in the searing Havana heat.

Eventually growing homesick for the US, Jack Johnson returned in 1920 to do his time, which, like most everything else he did, was on his own terms. Once freed, he boxed occasionally, took to the vaudeville stage, played bass on the New York nightclub circuit – pretty much did whatever he pleased.

Apart from wealth, women and fighting, Johnson’s great passion was automobiles. He met his death at the wheel in 1946, crashing after speeding in anger from a segregated diner in North Carolina where he had been refused service.

Perhaps as he drove away, Jack Johnson’s mind returned to a morning in Sydney, where the hammer blows he inflicted on Tommy Burns were the product of an unloving, unlovable America – a nation he conquered in spite of himself and to spite the majority of his countrymen.