To say that the Indonesian media is currently under duress would be an understatement. The declining state of press freedom over the past couple of years, signified by the rising threats and violence against journalists, and recent mass layoffs that affected thousands of media workers, have stunned the Indonesian [national] press.

But for a seasoned journalist like Wahyu Dhyatmika, this intensely challenging situation is a wake-up call for the Indonesian media to go back to its roots: serving the public.

Wahyu was appointed as the CEO of Tempo Digital in 2021 and, previously, he was the editor in chief of Tempo Magazine, and in 2015, led the Panama Papers reporting in Indonesia, the collaborative cross-border investigative project initiated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). He believes that there must be a silver lining to the gathering storms facing the press in his country.

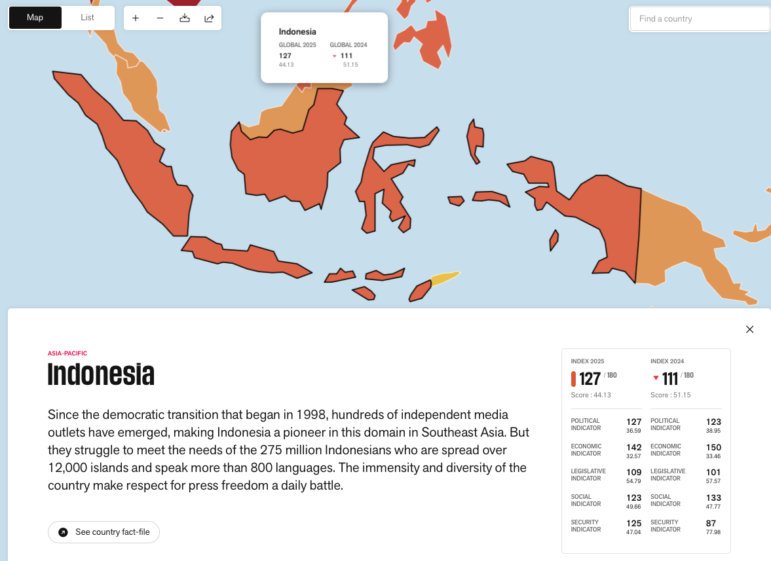

GIJN: The Indonesian Press Council found in its survey a declining trend in press freedom during the past two years. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) also highlighted a similarly worrying pattern since 2023. How do you see press freedom in Indonesia?

Wahyu Dhyatmika: I tend to agree with the indexes. I think the best indicator to judge how the press freedom condition has declined is the number of cases of violence or online harassment attacks against journalists in the last few years, which have increased.

Because I’m now a publisher, I can also see how the current ecosystem isn’t really set up to make sure that we have the freedom that we need as publishers. For instance, I talk a lot about this issue, how the business model of the Indonesian media is not really in line with the need to freely criticize the government and freely expose wrongdoing by public officials because most of the media rely on the government to make their business sustainable [by getting revenue] from local ads. Without any changes to this business model, without any changes in the ecosystem, press freedom will continue to worsen.

The 2025 RSF Global Press Freedom Index dropped Indonesia’s ranking 16 places from the year before, putting it into the “difficult” category. Image: Screenshot, RSF

GIJN: Aside from that, what do you think are the biggest factors that contribute to this decline in press freedom?

WD: I think that all of the factors are interrelated. Why is there more violence against journalists? Because there is less commitment from the media owners or the media companies to protect their journalists. They tend to pursue a more informal solution, like trying to reconcile the case by demanding an apology instead of getting the case to court. So there is no legal mechanism to make sure that this never happens again.

So I think there is a correlation between the lack of independent media in Indonesia and the decline of press freedom. And the lack of independent media in Indonesia is caused by the business model crisis, the media’s dependency on one revenue stream, which is the government.

GIJN: You mentioned in a previous interview with GIJN that one of the challenges of conducting investigative journalism in Indonesia is getting public data and documents from official sources. Has there been any progress regarding those challenges?

Veteran award-winning journalist Wahyu Dhyatmika is currently CEO of Tempo Digital. Image: Screenshot, ICIJ

WD: When you ask about the accessibility of data, accessibility of information, I think that’s more technical in the sense that, even if you cannot get official data or public documents, as a journalist you can go around that. You can use your networks. You can convince someone inside [to become] a whistleblower.

The factors that I mentioned are more fundamental. Without one of those, you cannot operate as an investigative reporter. So luckily, in Indonesia, we still have one, the legal support from the press law. But as for independence and the right business model, I think those two factors are not available to all newsrooms. I’m proud to say that Tempo is one of them, and I would like to see more newsrooms achieve all three factors.

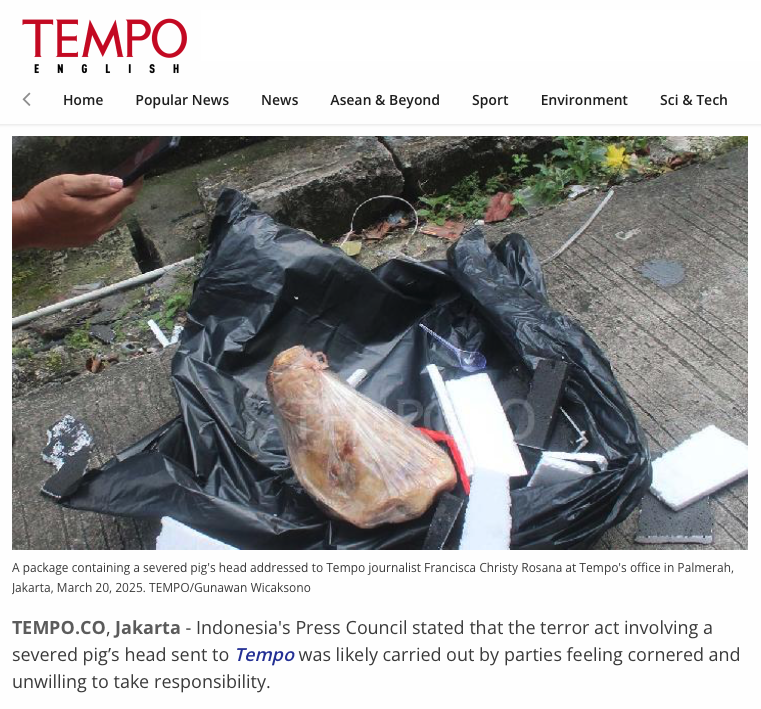

GIJN: Since the new government took office, we have seen several occasions where the work of journalists is being obstructed. For example, the president refusing to answer journalists’ questions and real threats sent to journalists like the one against your organization, Tempo. What do you think reporters, and the Indonesian media in general, should do to navigate these challenges?

WD: We did try some different methods as a strategy. We started the collaboration, IndonesiaLeaks, a couple of years ago, and it still exists today. There are more collaborative networks now compared to a few years ago. That helps prevent or at least mitigate potential backlash. Because if you do it together, then you have more eyes to check potential loopholes, areas that people might use to attack your story. You can also have more lawyers or more resources if you work together.

A Tempo reporter was the target of an intimidation campaign that involved sending a pig head to the news outlet as a threat. Image: Screenshot, Tempo

What I don’t think we do enough is try to rally public support for journalists. I think when the pig head terror threat happened [directed at a Tempo journalist], we got a lot of support. We received, I think, more than a dozen flowers in our office. We put them on in front of the office to show that the public is behind us, and it’s really touching. It’s really something that we deeply appreciate because it shows that we are not alone, and it’s really strengthened the newsroom, especially for the journalist who got the threat.

A few weeks after that, we did an online gambling story and mentioned a prominent public figure’s name. And we got a DDoS attack this time, which almost crippled our website. But we were not able to gain the same attention because it wasn’t physical, and it was harder for people to see how traumatic that kind of attack was.

GIJN: Recently, a lot of news organizations in Indonesia have experienced mass layoffs. How do you think this situation affects the Indonesian press and Indonesian press freedom in general?

WD: I think we are facing one of the worst conditions, business-wise, for the media since the pandemic. To be honest, the trigger for these mass layoffs is tied to the government’s policy to reduce spending on the media.

It’s a wake up call for the media sectors that you need to diversify your revenue stream.

If you go to any district or province and go to the media offices, you will find that, on average, I think 80% to 90% of the revenue comes from local government spending. And whenever they start criticizing the local government or the mayor or the governor or the district head, immediately their contract will be terminated.

You cannot let one party basically say, if you receive advertising money from us, you cannot criticize us. That’s what basically happened with government spending in Indonesia.

So in a way, by losing that kind of revenue stream, well, you can say that there’s a silver lining that this might be the time for the media to start doing journalism in the correct sense. This might be a make or break moment for Indonesian media.

GIJN: You mentioned earlier that the Indonesian media industry is struggling to be profitable. What is Tempo doing to navigate this challenge?

WD: I think from early on, we realized that our biggest asset is our journalism, and investigative reporting, hard-hitting stories on scandals, on things that [expose] wrongdoings that really involve public interest. That’s our most significant asset.

Gradually, as we improve our technology, we improve our users’ experience, we build the capacity of our technology team, then we can start to harvest that loyalty into subscription as a revenue stream. And that’s what we’ve been doing in the last five years. We steadily built our subscription business, and I’m happy to say that it’s been growing in the last two years, and we are optimistic we can reach 100,000 subscribers in the near future.

With at least 100,000 subscribers, we will be able to independently support our newsroom. And with that amount we don’t have to rely on advertising.

GIJN: With media companies trying to reduce production costs, do you think that investigative journalism, which is considered high-cost, still has a future in Indonesia?

WD: High cost is not an issue if you have high revenue. High cost is only an issue if you cannot monetize [it], if you don’t have the business model to convert that product into monetary value. So, I don’t see that as a problem. Is investigative reporting costly? Yes. Does it take a lot of time? Yes. But once you have it, once you publish the story, the impact that it creates, the surge of subscribers that happens once people see it is enough to compensate for all the time, cost, money, energy that you put into it.

There are plenty of ways to finance an investigative story. You have a lot of grants now available. You can engage with the right partners to reduce costs. You can collaborate, cross borders. You can work with different strategies if you don’t have the right amount of money you need. So there are plenty of ways around it.

The most important thing to have is the motivation to serve the audience, the public. If you don’t have someone to do this watchdog reporting, to act as the eyes and the ears of the public, then society as a whole suffers.

We always believe in this saying at Tempo: ‘We make money by publishing stories.’ We make money so we can keep our newsroom independent and keep publishing investigative stories. That’s why we need to be profitable. We are not creating stories in order to get money. We are making money to print stories. So the mindset has to be right.

GIJN: Journalists are having to adapt how they work to stay relevant. What are the skills you think Indonesian journalists need to master in order to survive in this industry?

WD: I think the ability to really connect to your audience, to really engage with your audience using all means available in this digital age. The media is no longer a faceless entity that only consists of brands, like Tempo. Tempo is a brand, a name. But what is Tempo without the persons behind it?

So we need to put faces in our story. So that’s why when we did the Bocor Alus podcast, we had a lot of positive feedback because finally people can relate to us and can see the personalities behind Tempo. That attracts a lot of young people, the Gen Z, the Millennials, a younger audience.

They don’t see Tempo as a legacy brand, as an old magazine that only their fathers and parents read, they can see that it’s also on socials. They are with us in every story. Bocor Alus is an innovation that was born from within our newsroom, because we let our reporters and editors experiment with all sorts of ideas.

Journalists in Bandung in 2024 protesting against proposed changes to press laws in Indonesia. Image: Shutterstock

GIJN: With threats and rising violence towards journalists, what are the tips that you have for journalists in Indonesia, especially those who want to do investigative reporting?

WD: So, threats and violence can happen in different types of situations. Most of the cases that we see lately happen during public protests.

But if you are investigating someone or a story, there’s plenty of planning that is necessary, to make sure that you are safe. Communication with your editors and your colleagues in the field is important, and knowing who has the motive to harm you is also important. So, doing risk mitigation assessments.

And there are a lot of training modules, [like those] at GIJN and also in local associations like the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) that provide all the necessary information that you should know before doing any sensitive story. But I think if you ask me what’s the best skill to have it is to be prepared.

You have to always assume that if you’re doing a sensitive story, there must be some dangers. It is not paranoid to assume that. But you need to be able to to really understand who is the one that poses the higher risk to your job.

GIJN: What hopes do you have for the Indonesian press in the near future? And is it exaggerating to say that the current situation is bad, or dire?

WD: I think we still have hope to see better conditions. I think one of the factors that created this situation is our internal inability to find the right business model.

And I think the situation was worsened by the budget cuts — the government’s policy to link advertising with editorial policy — something that should not be done by a democratic government. I think that’s a big red flag for our government for doing that. But you can still survive if you have a loyal audience supporting you.

And the audience will support you if they trust you. And they will trust you if you’re doing good journalism. The problem with us is we have not been doing our job properly in the last few years. I’m not saying the whole media is not doing their job. We dig our own grave by not, you know, really putting our audience’s needs at the heart of what we are doing.

We let the business managers decide this is the right business model, this is the right story… and we don’t really listen to what our audience needs. So I think that’s the first thing that we need to do.

We need to do the best journalism we can do for the audience. And, and if the audience supports us, there’s nothing you cannot do. There are a lot of examples where the public will rally behind you if you do your job properly as a journalist or a media company. We tend to forget that our biggest stakeholder is our audience. We forgot that we need to keep that trust.

Ramadani Saputra works with the audience engagement team at The Jakarta Post, and is responsible for managing the day-to-day social media operation for the editorial team. Before that, he spent more than two years reporting and writing for the sports desk at the Post and previously worked at Dunia Kita – Voice of America. Born and raised in Bandung, West Java, he graduated from Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia (Indonesia University of Education).

Ramadani Saputra works with the audience engagement team at The Jakarta Post, and is responsible for managing the day-to-day social media operation for the editorial team. Before that, he spent more than two years reporting and writing for the sports desk at the Post and previously worked at Dunia Kita – Voice of America. Born and raised in Bandung, West Java, he graduated from Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia (Indonesia University of Education).