A collection of images curated by the director tells the story of protest and resistance in Britain. But who wins and who loses is only part of the story

We live in a time of resistance – everywhere you look, people are protesting: against war, against corruption, against the abusive politics of their own governments. Which makes Resistance, an exhibition of images curated by the director Steve McQueen, all the more resonant.

In the book that accompanies the exhibition, McQueen recalls the moments in his life when he first grasped the idea of resistance, and its importance. His childhood neighbour, a man named Milton, “would always post various newspaper cuttings in an envelope with my name on through our door,” he writes. These included clippings about the miners’ strike, the revolution in Grenada, and the campaigning singer Paul Robeson. “He was the person who helped me ask who?, how?, why?, and what?”

The images in this exhibition, which span the 20th century and cover a wide range of different movements, push the viewer towards precisely those questions. In a stark black and white image of hunger marchers, taken in 1934, one protester carries a banner reading: “Abertillery workers refuse to starve in silence.” This was a period in which Britain had global superpower status – and yet people were starving in the valleys? The nostalgic view of Britain’s golden era does not – and cannot – contain such brutal details. How? Why?

The images are, as is to be expected with McQueen’s involvement, both provocative and aesthetically brilliant. Eddie Worth’s image of an anti-fascist demonstrator being arrested at the Battle of Cable Street in 1936 is an example of near-perfect photographic composition.

In Christine Spengler’s Girl at IRA funeral procession, a skinny girl stands in the street, holding a flag, staring straight into the camera. The white lines of the road take the eye into the background and to the hulking military barricade, slightly out of focus, that waits behind her.

In another image, a Durham mining family is pictured at home in the lounge. A poster on the wall bears the image of Karl Marx, while on the TV is the unmistakable face of Arthur Scargill. The woman sitting on the floor gazes reverently at his image on the screen.

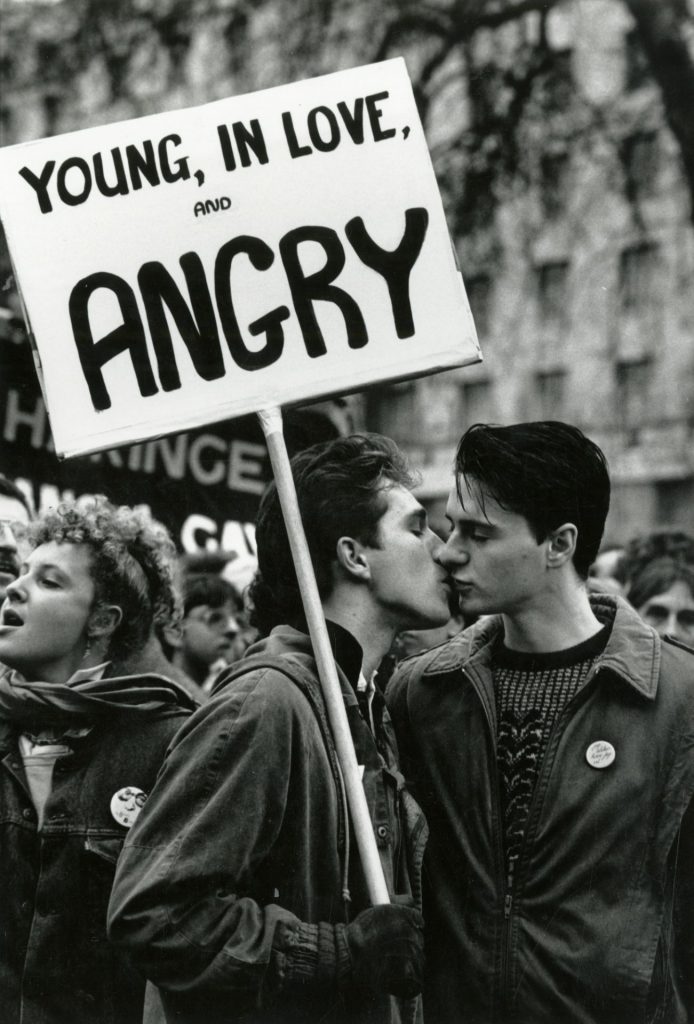

The images act as a reminder that human progress depends, sometimes, on a willingness to resist. Resistance, as defined here, is a physical act, a fact that is often overlooked, especially now that so many contemporary activists confine themselves to social media posturing.

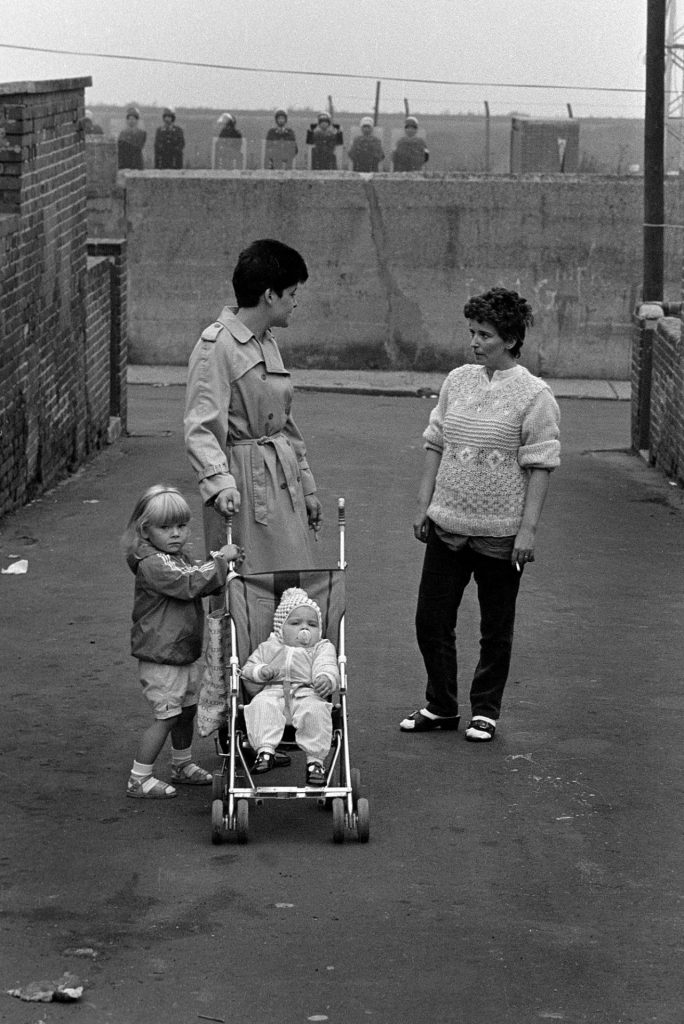

The miners resisted – and eventually they lost. And yet their acts of resistance still resonate with us now, and are poignantly captured in several of the images here. Contained in those photographs is the deeper lesson of this powerful and moving array of images: that, win or lose, through resistance there is dignity. As such, to resist becomes an end in itself.

Resistance is at the National Gallery Scotland, Edinburgh, from June 21 until January 4