As I went into the hotel’s internal missile shelter, I wondered whether the people involved in both sides of this war truly understand what they stand to lose from it

There had been rumours all day Thursday, after the US government announced they were removing non-essential personnel from Iraq and other locations in the region. People were contacting relatives in government and in the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) to ask if this was “the big one” that the populations of Israel and Iran had been waiting for. At 3am on Friday morning people had their answer.

I was woken by air raid sirens sounding across Tel-Aviv, followed shortly after by the alarm in the hotel. An automated voice instructed me to move to the internal missile shelter that nearly every building in the city has. For those caught in the open there are public shelters dotted around and all buildings with shelters open their doors to allow people to enter and take cover. Instead of sirens, the residents of Tehran were awoken by the sounds of Israeli rockets hitting the city.

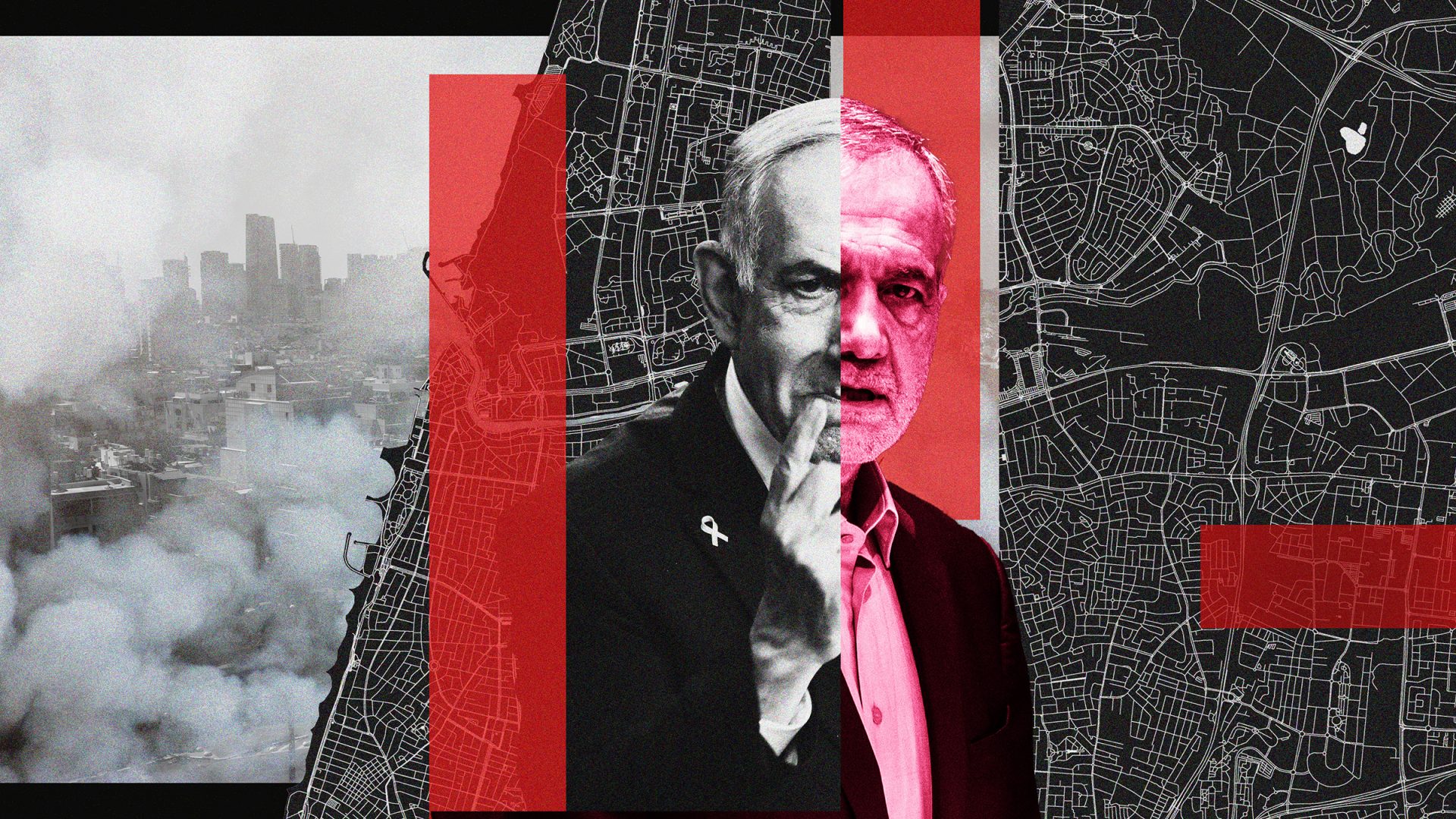

Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has described Israel’s attack on Tehran as “a targeted military operation to roll back the Iranian threat to Israel’s very survival”. The nuclear facility at Natanz seems to have been a particular focus. Netanyahu stated that the operation will continue for “as many days as it takes to remove this threat”. Masoud Pezeshkian, the president of Iran, has called Israel’s waves of air strikes a declaration of war and warned Tel Aviv that their “powerful response will make the enemy regret its foolish act”. Supreme leader Ali Khamenei has warned Israel that it faces a “bitter and painful” response.

Iranian state TV reported the deaths of six scientists, as well as civilians, including children. This has not been independently verified. The IDF says it carried out strikes on nuclear sites and says Islamic Revolutionary Guard chief Hossein Salami and other commanders were killed. None of the one hundred Iranian drones launched at Israel in retaliation reached their intended targets. Unlike the Iranian drones used by Russia that are being fired at Kyiv in increasing numbers, the majority launched against Israel were intercepted.

Hotel receptions were busier than usual at 5am when the “shelter in place” restrictions put in place by Israel’s home front command were lifted. People were rushing to check out so they could leave the city. I had to stay, as all flights were cancelled – airspace above Israel, Jordan, Iran, Iraq and Syria was immediately shut. El Al removed some of its planes from Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv as a precaution, in case the airport was hit.

War’s worst consequence is the severing of connections. There is the temporary separation of people stuck on the wrong side of closed borders, people interned by authorities and people conscripted or compelled to do their duty on the battlefield. Then of course there is the separation of death. Recent events will create separations of both kinds.

Walking through Tel Aviv on Friday afternoon there was a veneer of normality. Businesses were open and people were moving around freely. Missile alerts are a fact of life here. They sounded in Tel Aviv on Tuesday as the Houthis fired rockets from Yemen. When the wind blows from the south it is possible to hear explosions from operations in Gaza, 50 miles away. These detonations seem to be largely ignored. The destruction and death they are causing seems a world away from the open air bars and the beach-side restaurants.

That veneer seems slightly thinner. Further alarms are expected. Complex formations of large numbers of drones and missiles fired from Iran will test Israel’s air defences. This will be especially testing if Iranian attacks are coordinated with the Houthis, and pro-Iranian groups in Iraq and Southern Syria.

The ability to terrorise the population of another country through long distance air strikes is a relatively modern capability developed rapidly during the first half of the twentieth century. The first documented aerial bombardment in war was in 1911, during the Italo-Turkish War. Italian second lieutenant Giulio Gavotti dropped four grenades from a monoplane over a Turkish camp in Libya. By the 1940s cities across Europe were being carpet bombed. The Second World War effectively ended with the aerial, atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They thankfully remain the only use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict.

It is a unique form of terror: the helplessness of sitting and waiting for an unseen, faceless, projectile to land and detonate, with its shards of burning metal and lung-exploding blast wave. Your survival is down to luck. In order to reduce the risk of a nuclear attack, Israel is inflicting precisely this terror on the people of Iran. But in doing so, it had increased the risk that this terror will be visited on its own people.

The Israel foreign ministry has issued instructions to Israeli embassies around the world to close and stated that consular services will not be provided. The ministry has advised all Israelis abroad to fill out a survey to update the ministry on their location and situation. As we have seen with the recent attacks in the US, the risks to people from this conflict are not limited to the Middle East.

While there are many dissenting voices within Israel concerning Netanyahu’s handling of the war in Gaza, there is an almost universal level of support for a war against Iran. Iran’s nuclear program is seen as an existential threat. The fear is genuine.

We are united by our mortality. This is intrinsically linked to the idea that justice requires reciprocity of risk in war. Philosopher Paul W Kahn argues that the combatants possess the right to injure each other “as long as they stand in a relationship of mutual risk”, which has relevance for the asymmetry of the military technology between Israel and those it is fighting.

Sitting in Tel Aviv listening to the bellicose statements of the leaders on both sides of this rapidly escalating war, it is impossible not to think about mortality. Instead of focusing on what technology and what weaponry the respective militaries have, I hope more of the participants recognise the relationship of mutual risk that they are in. Now more than ever, we should focus on what everyone in the region has to lose: all of those connections which can be broken, sometimes temporarily, but increasingly and tragically, forever.